Clinical incident management

NMHS strives to deliver high quality, reliable and safe care to every patient, every time, everywhere. Despite our best efforts, occasionally a preventable clinical incident may occur. It is important that our health service learns from these cases to create a safer environment for our patients.

By fostering a culture of no-blame and continuous improvement, all staff are supported to speak up for safety. If a patient’s safety is compromised, NMHS staff are encouraged to report and learn from these clinical incidents or errors.

NMHS uses Datix Clinical Incident Management System (CIMS) to record and manage clinical incidents occurring in its sites and services. We monitor and report clinical incident trends to staff and committees.

So that the health service can adequately investigate the causes of clinical incidents, each incident is assigned a rating known as a Severity Assessment Code (SAC) score that guides staff in the type of investigation method to be applied to each event. Clinical incidents that result in serious harm or death (SAC 1) require a very detailed, rigorous investigation facilitated by an expert panel which may include members independent to the health service.

How we are doing

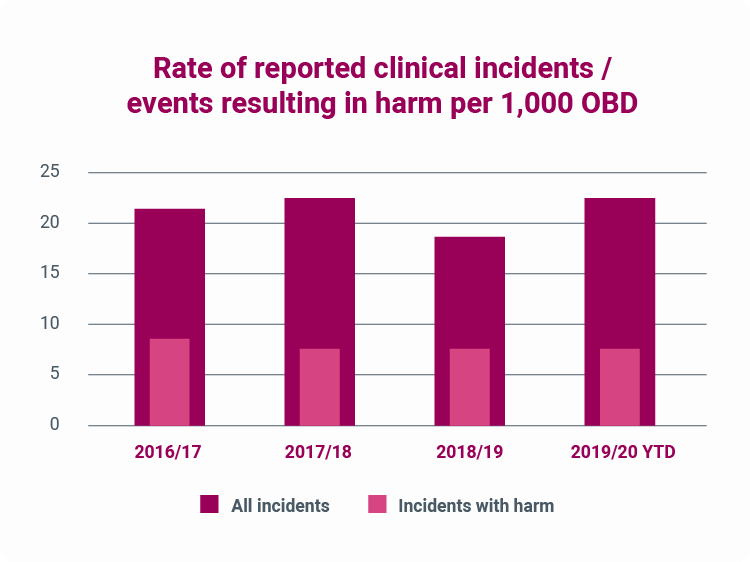

The graph below shows the combined incident rate for NMHS:

- Sir Charles Gairdner Osborne Park Hospital Care Group

- Women and Newborn Health Service

- Mental Health, Public Health, Dental Services

Chart: NMHS rate of reporting clinical incidents per 1,000 occupied bed days – All reported inpatient clinical incidents and inpatient clinical incidents resulting in harm.

What the figures mean

The graph shows the rate of reported inpatient clinical incidents per 1,000 bed days. The maroon columns show the rate of all inpatient clinical incidents, and the pink columns show the rate of incidents that resulted in harm of any kind.

The higher total rate of reported incidents and the consistently high rate of reporting show that the culture of reporting incidents is healthy and effective. Note that the rate of incidents resulting in harm has remained low – this shows that the health system learns from events and introduces effective programs to prevent and minimise harm resulting from incidents.

Learning from a serious clinical incident

At NMHS, patient safety is our priority. Any clinical incident that occurs is reviewed so we can learn from it and improve the quality of care we provide. For any incident that results in serious harm, a robust investigation and analysis of events is undertaken by a panel of experts who will explore contributing factors, identify the root causes, and recommend actions to prevent harm and promote service improvements.

NMHS provides a series of educational modules for staff who contribute to this process to ensure that a culture of safety is promoted and maintained. These include:

- Root Cause Analysis (RCA) Overview

- Report Writing

- Recommendation Development

- RCA Facilitation and Timeline Development

- RCA Interviews

- Learning from clinical incidents

- Managing a multi-site review of a clinical incident.

An example of lessons learned

Situation:

The incident involved a 93-year-old female who was admitted for treatment of left leg cellulitis. The patient was sent home with oral antibiotics. She returned four days later at which time her daughter explained that she had not been taking the antibiotics. During this second admission, the patient got up from her bed to go to the toilet and fell. She sustained a fractured distal radius and ulnar of her left wrist and a minimally displaced intertrochanteric fracture of the left hip requiring surgery.

Investigation:

A Root Cause Analysis expert panel, composed of senior medical, nursing and allied health, was formed who reviewed the patient’s medical records and relevant policies. The Panel also spoke to the patient and staff members involved in the incident regarding their recollection of events. A detailed timeline was established which identified potential improvement opportunities.

Contributory factors:

The Root Cause Analysis panel focused on the patient’s risk factors and the implementation of falls risk reduction strategies. On these points the panel concluded that the patient’s medications were appropriately managed but agreed there were a few missed opportunities to provide a formal cognitive impairment assessment. There were numerous references to the patient’s fluctuating confusion including her being “pleasantly confused”. A formal assessment would likely have provided the required triggers to implement additional falls prevention strategies that may have resulted in the prevention of this incident.

Recommendations:

The key recommendation proposed involved the development of a plan to promote and implement the Cognitive Impairment Management Policy - requiring a cognitive screen to be undertaken on admission using a validated assessment tool for any patient over the age of 65 years.

Lessons learned:

The key lesson learned related to correcting the perception of low or no risk associated with patients who are “pleasantly confused”.